Finding home in Art Deco

I marvelled at Art Deco architecture across the world, only to realize that what I was looking for was right at home.

When I began thinking about this piece, I thought it would speak to my recent trip to Morocco and how fascinating I found the architecture in Casablanca. My travel partner and I were marvelling at every other building along the streets we were walking through, impressed by the designs. I felt a sense of familiarity that I couldn't fully understand or articulate. I later realised that it reminded me of Bombay, my hometown, and in particular Matunga, the neighbourhood where I grew up and spent most of my life. It prompted me to research the history of my neighbourhood, its architectural and urban planning significance, combining it with the oral histories and lived experiences of its residents.

Until recently, I had a notional understanding of and general interest in Art Deco, knowing that many examples of this style exist in Mumbai, from the iconic buildings in South Bombay (what we call the “town” area) and towards the centre, residential buildings in Matunga and Dadar Parsi Colony. I wasn’t prepared, however, for the waves of thoughts and emotions that would emerge from understanding the history of the lane I grew up in, and after discovering that my family home is in fact an Art Deco building. It started two weeks ago, when I discovered that my family’s building is listed in the Art Deco Mumbai inventory, while I was on the website researching this piece. My father, always the most supportive, promptly reached out to his friend, Ajit Rao, a talented architect, animator, and artist who also lived on our street in Matunga, so that I could ask him a few questions. It turned into a captivating discussion, making me deeply aware of the heritage of my lane, and of Art Deco’s proliferation in Bombay.

Growing up in Matunga

I grew up on R.P. Masani Road in Matunga, behind V.J.T.I. College in the Five Gardens area. I have always maintained that Matunga is the best neighbourhood in the world. While it may sound facetious, it was (unknowingly) rooted in the fortuitous coincidence of living in one of the earliest planned neighbourhoods in Mumbai.1 Our lane was lined with beautiful small apartment buildings on either side, “ground + 2 or + 3” structures for the most part. Five Gardens was lush with trees and parks and had wide roads, where I would often go for long walks and bicycle rides with my father. Matunga market, still one of the best in the city, had every manner of household items, fresh produce, and South Indian food that one could want, and several good schools, colleges, and a cinema were within walking distance.

As a child, I had anecdotally heard of the film industry connection of R.P. Masani Road, primarily the fact that starting from the 1940s, 4 generations of the Kapoor clan lived there, along with Manmohan Krishna, Madan Puri and their respective families. I was close to Manmohan Krishna’s wife, Rajeshnandini, whom we affectionately called Kiki aunty (Kiki aunty was so impressive, knowledgeable, warm, and loved by everyone; she deserves a post on her own). I also remember seeing veteran actor Amrish Puri in my parents’ wedding reception photos (and thinking to myself, maybe my parents are cool). More recently, through the conversation with Mr. Ajit Rao, I discovered that several other film industry artists lived on R.P. Masani Road, including some of my maternal grandfather’s favourite singers - K.L. Saigal and Manna Dey - and actor K.N. Singh; all of this earned the street the nickname “Hollywood Lane” (A fun fact that I discovered in researching this piece - my maternal grandfather briefly lived in my lane too in 1942). Mr. Rao and my father had several interesting anecdotes to share. According to my father, while he was growing up, from the 60s to the 80s, the homes in the lane felt like one big family, and both quotidian life and festive occasions were enjoyed with equal enthusiasm. Both men remember that during Diwali, the Kapoor brothers would round up the lane’s kids, asking them to arrange ‘anars’ (firecrackers) in a line across the length of the street such that the whole lane would be lit up at once. During Ganesh Chaturthi, Mr. Rao spoke about a young Mithun Chakraborty doing dance performances in his (now) signature drain-pipe pants at the events held in the “back lane” (funnily enough, which lane was back lane depended on your vantage point - residents from R.P. Masani Road and the V.J.T.I. street would each call the other back lane, something I remember from my own time too). Televisions were rare in those times, and Manmohan Krishna was the first to get one, which usually meant that everyone would gather at their house. Sometimes this meant that their house was so crowded, Ajit Rao chuckled, that they would leave. Mr. Rao also remembers the film ‘Bees Saal Baad’ being played on a projector on the terrace of Amar Kunj where lane residents would gather to watch, on each side of the screen. On his son’s birthday, Manmohan Krishna sang his famous song - Tu Hindu banega na Musalman banega - on the terrace of their building. At an event, Raj Kapoor showed off his bhangra moves standing atop the pillar at the entrance of my family’s building.

On Bombay’s Art Deco heritage

Perhaps the hardest-hitting realisation from my conversations with Mr. Rao was that the most beautiful building in my lane - Gold Finch - was designed by none other than Gajanan B. Mhatre. Mhatre was a prolific architect and professor with a career spanning roughly 40 years, responsible for many of the iconic Art Deco buildings that define Mumbai, including Empress Court and Soona Mahal in South Mumbai, and lesser-known but equally stunning buildings, as I am discovering now, in Matunga and Dadar.

I have never seen the inside of Gold Finch, but remember it as the most striking building in the lane, and being one of our favourites to play in as children. Interestingly, living in the building also left a lasting impact on Kamu Iyer, whose family moved to Gold Finch when he was a child, in turn influencing him to pursue a career in architecture, starting with studying at Sir J.J. School of Arts, where he was taught by Mhatre. Kamu Iyer himself became one of the greatest modernist architects from Mumbai, working with stalwarts such as Charles Correa. In fact, my father’s alma mater, the S.P. Jain Institute of Management, was designed by Mr. Iyer. I don’t remember ever interacting with him, and knowing about him and his legacy now, it feels like a great loss. Dad remembers taking morning walks occasionally with him at Five Gardens, where Kamu would tell him how the old underground drainage system of Bombay was perfectly designed to take water smoothly to the sea.

Mr. Rao connected me with his friend, Mustansir Dalvi, an architect, professor, author, and one of the trustees of Art Deco Mumbai. Mr. Dalvi had his own association with R.P. Masani Road. Kamu Iyer’s son and Mustansir Dalvi were classmates at the J.J. School in the 1980s, and Mr. Dalvi would often visit their house. For a student of architecture, Mr. Iyer’s expansive flat in Gold Finch, with its interconnected rooms, big windows, and large cantilevered balcony, was impressive. Mr. Dalvi’s association with Kamu Iyer, both professionally and as friends, continued after graduation, alongside the memory of Gold Finch which was equally central. Mr. Dalvi’s interest in this style emerged in part through his association with Kamu Iyer. It was also shaped as a result of growing up in Pune in an Art Deco building (as he realised only later), and seeing the Art Deco heritage ubiquitous to Bombay. Over the last several years, he has made extraordinary contributions to capturing and preserving this heritage of the city. Academically, he sought to analyse the environment in which Mhatre’s buildings came up, uncovering the signs and symbols that Art Deco buildings evoke, and wrote his doctoral thesis on the semiotics of Art Deco architecture. The style celebrates 100 years this year, and its origins are traced back to the 1925 exhibit - the ‘Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes’ in Paris. What is now known as Art Deco was, in its time, simply referred to as ‘Style Moderne’, gaining the moniker decades later.2 Art Deco was not developed very coherently, and grew almost simultaneously across the world in the 1930s and 40s, as a result of improved travel and communication. It was a modern style that was different from the architecture of the past, allowing architects and designers to freely experiment. It was characterised by its structural form and elements such as the ziggurat (stepped profile), a central structure emerging towards the top flanked by identical wings on either side, streamlining and nautical designs such as porthole windows and railings (inspired by locomotives and oceanliners, known as “style paquebot” in French), and seemingly oppositional characteristics such as curved forms and sharp, geometric lines. The style was seen as aspirational and a sign of upward mobility.3 In India and Bombay4, the style was adapted locally, becoming known as Indo Deco or Bombay Deco,5 with elements such as tropical motifs including sunbursts and ocean waves, Indian designs and lettering, and ornate grille work and nuancers.6 Art Deco’s proliferation in Bombay7 and in the country can also be traced to a new construction material that emerged in the 1930s, Reinforced Cement Concrete (RCC), well-marketed by cement companies, allowing for the development of striking features such as cantilevered balconies, a prominent fixture in residential Art Deco buildings in Mumbai, where the balcony is jutting out of a building, seemingly suspended in air.

Art Deco lettering is just as unique, and in India, often reflects local sensibilities with the use of Indian scripts (Devnagari or Gujarati, for example) and the use of different materials such as stucco to create letter forms. I connected with Tanya George, a type designer and educator who worked on the restoration of the Empress Court signage. She discussed architectural lettering, where the lettering is integrated into the façade or relief8 work of the building itself, making it difficult to destroy, signalling the longevity and endurance of houses passed down for generations. Lettering provided yet another dimension for architects and landlords to carve personalisation into the design of the buildings.

Working on this article prompted me to ask my father about the history of our building. Built in 1939, then called ‘Shirin Cottage’, the building was purchased by my paternal grandfather and his brothers from a Parsi gentleman in 1956, and was subsequently renamed after our family. The period in which the building was constructed, its foundational structure (a vertical central spine with two identical wings on either side, and a flat roof), curved cantilevered balconies, compound wall with ornate grille work, and decorative elements enhancing the shape of the building make it clear that it is an Art Deco building. The fish-scale design on the façade is likely dressed masonry, in Mr. Dalvi’s opinion, in which stones were shaped into parts and then built into walls. I could very well still call it a fish-scale design, Mr. Dalvi said, because Art Deco only emerges out of practice, rather than any formal codification.

The grilles right outside the windows did not always exist, and our building was one of the few to have the “otla”, a raised open platform (that our family called the “thada”), where Dad, Ajit Rao, and others would play table tennis. During one such game, Mr. Rao remembers running into Rishi Kapoor, who was a close friend of Mr. Nanda, who lived upstairs. Kapoor’s film ‘Mera Naam Joker’ had just been released then, and Mr. Rao still remembers the pleasant interaction with him.

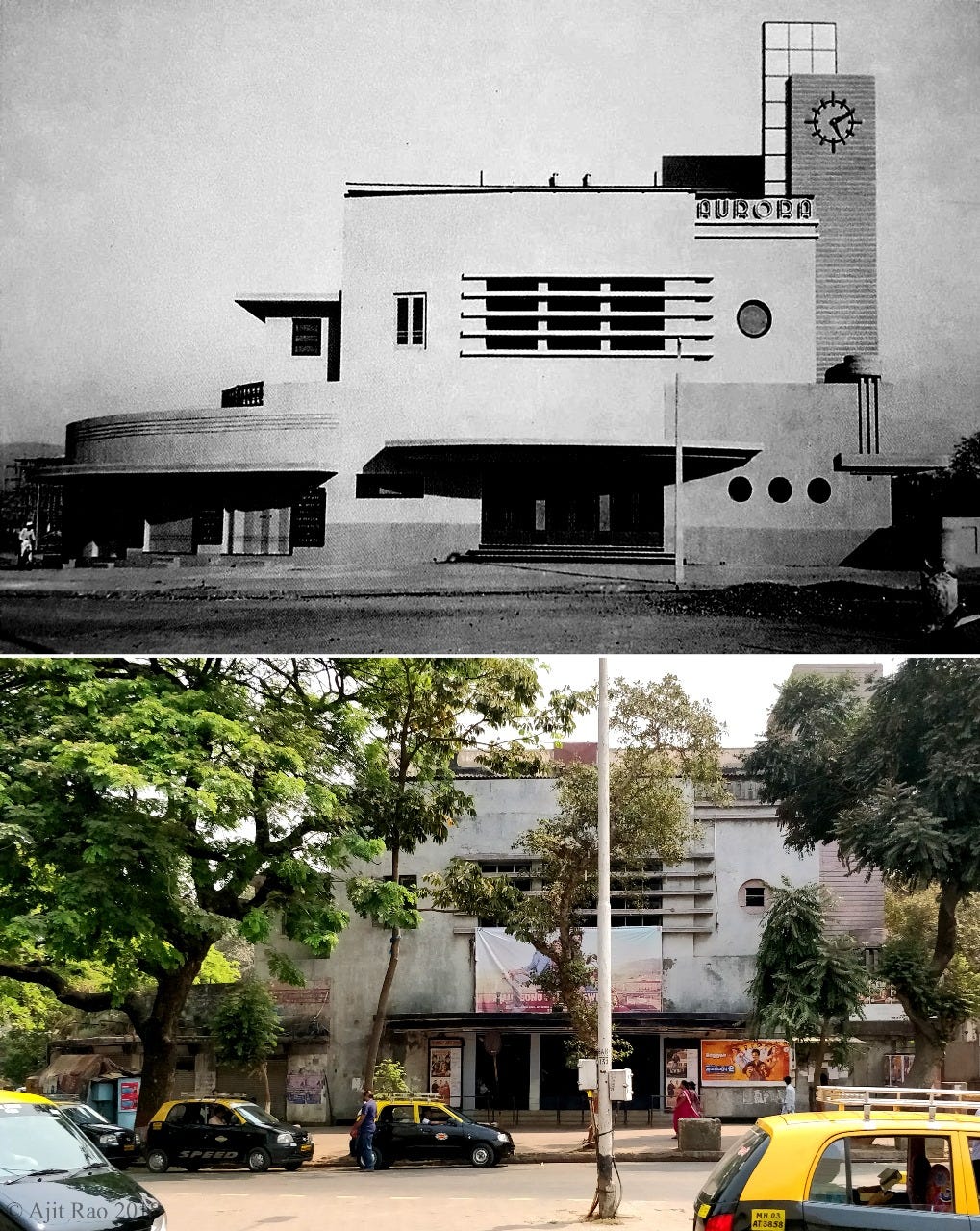

For an area that had a strong early connection to Bollywood, the lack of care afforded to the Aurora theatre (which was known to all of us as “Arora”, in a funny Punjabi-fication of the name) has surprised me. I distinctly remember the interior of it, but had never known how beautiful and striking the exterior looked, especially at the time of construction, until Mr. Rao shared this photo with me. For as long as I can remember, the outside of the theatre was in a state of disrepair and its most iconic design elements that I can now see in the photo were hidden behind film posters. My maternal grandfather remembers when the theatre was being built in 1940, and that he saw the first movie shown there, “Sikandar”, starring Prithviraj Kapoor.

Art Deco’s influence also extended to places of worship. In fact, the ‘akhada’ or wrestling ground where my maternal grandfather practised was located near Datta Mandir, also designed by G.B. Mhatre.

Preserving Mumbai’s Art Deco heritage

The city planning schemes developed in the 1920s by the Bombay Improvement Trust to build new neighbourhoods ensured sufficient light and space between buildings, and adequate public spaces such as roads and parks.9 This coincided with the rise of modern forms of architecture such as Art Deco, enabling the Matunga, Dadar, Parsi Colony, and Shivaji Park areas to develop in unique ways, combining both form and function. Mr. Rao and my father reminisced that in their time, people spent a lot of time in the lane. This is something my brothers and I felt too while growing up. I am reminded of Kamu Iyer’s point that planned precincts, or indeed any urban spaces, acquire vibrance and meaning only when residents occupy them and give them character. Nakshatra Borgaonkar, an art historian and heritage educator who has been leading exploratory walks for the last 2.5 years, also spoke to me about the importance of documenting and archiving Art Deco architecture, particularly Bombay’s lesser-known heritage around Shivaji Park, as an example of more democratic and middle-class urban expressions of Art Deco, rooted unapologetically in Marathi culture, something that is highlighted beautifully by authors such as Shanta Gokhale.

Much has changed at R.P. Masani Road and in Matunga in the last decade or so. Gold Finch has been demolished, and I had a visceral reaction of sadness, realising that no good photos of it exist online. The lane looks different every time I go back to Bombay, with changing redevelopment legislation not only in the neighbourhood but across the city. Mr. Dalvi stated that R.P. Masani Road was the most beautiful lane in Bombay, and I am inclined to agree. Big towers have replaced the planned small buildings, completely changing the scale of the neighbourhood. The lane and its buildings should have been preserved as a grouping and an intangible heritage, in his opinion.

I recently walked around my current neighbourhood in Toronto, and posted some photos of Art Deco buildings nearby (Toronto has a small collection). A friend of mine, Deane de Menezes, instantly reacted to this, saying it reminded her so much of Bombay. Art Deco is so intrinsic to the collective imagination of Mumbai that we sometimes take it for granted. It almost feels like it is hidden in plain sight. A resident of Wadala in Mumbai, Deane also noted that the neighbourhood is changing so rapidly with growing towers that it feels like all the light is blocked.

These reflections have not only been a nostalgic look at the days gone by, but are rooted in very real experiences of how we interact with the built form and environment, and what makes our neighbourhoods and cities liveable and enjoyable.

If you have stayed with me up to this point and would like to learn more about the fascinating world of Art Deco, here is a curation of resources:

All of Mustansir Dalvi’s writing and talks on the subject. A selection to start with: The Architectural Growth of Art Deco in Mumbai.

Art Deco Architecture in India (not just Mumbai)How Mumbai’s architecture evokes the sea

Mumbai’s architecture is losing its poetryKamu Iyer’s notable works: Buildings that shaped Bombay, the works of G.B. Mhatre, and Boombay, from Precinct to Sprawl, which I think should be mandatory reading for anyone from Mumbai. Dalvi also interviewed Iyer about the book.

A lovely Times of India piece on Kamu Iyer and Gold Finch.

A great primer on Art Deco terminology.

Not Art Deco, but you can enjoy a selection of K.L. Saigal’s most famous songs, to share in the joy that my maternal grandfather finds in morose music, which he has passed on to me:

Jab Dil Hi Toot Gaya

Ghum Diye MustaqilA biography of Madan Puri, written by his son Kamlesh Puri.

Art Deco Society of New York: https://www.artdeco.org/archives

Iyer, Kamu. 2014. “Boombay: from Precincts to Sprawl”.

Before the wave of Art Deco, Bombay primarily had Victorian Gothic, Neoclassical, and Indo-Saracenic architecture.

https://www.artdecomumbai.com/research/deco-dekho-bombay-deco-and-its-element/

Enhancers and nuancers are terms coined by Mustansir Dalvi to refer to the elements of Art Deco that either enhance the existing vertical or horizontal lines of a structure or add decorative nuances in terms of ornamental designs. See this talk by Mr. Dalvi for a detailed understanding of Mumbai’s Art Deco.

Art Deco Mumbai’s current count of Art Deco buildings in Mumbai stands at 1022 (as of 2023), meaning that Mumbai has more Art Deco buildings than Miami, but the collection is not officially recognised.

Relief is a design technique where sculptures or designs are raised above the background. “Bas-relief”, French for “low-relief”, is when the designs are only slightly raised, commonly seen in Art Deco.

There was a period of improved city planning in 1896 following the plague. This was done to promote better living conditions that allowed for light and ventilation.

Neha,

Wow!! This is such a well researched and articulate article. I would have never known any of this history of the area, despite going to VJTI for 4 years, with your dad, Rajiv, who you mention in your article. Had to read it twice to just absorb all the information. Great memories for me from 1977 - 1981.

Sarosh

Wow Neha . Such an interesting article on Mumbai's Art Deco buildings. And best of all our own Sethi Nivas is covered as an Art Deco building too.